5 Examples of Unique Selling Proposition (USP) That Built Global Brands

Here are 5 examples of unique selling propositions changed industries. Learn what makes a USP truly unstoppable.

What if a single phrase could transform a struggling startup into a billion-dollar business empire?

Sounds like a fairy tale, right? But it’s not.

The secret weapon behind some of the world’s most successful brands isn’t always massive budgets.

At times, it’s not even the best product.

It’s that unique value that makes them a purple cow in a field of monochrome Holsteins.

Marketers call it a unique selling proposition.

The big “WHY” statement that makes customers choose them over everyone else in their market.

In this article, we’ll explore 5 great unique selling proposition examples that made multibillion-dollar global brands.

We’ll look at their historical background, the market landscape that gave birth to them, and how they disrupt markets and reshape entire industries.

USP Example 1: Nike – Just Do It

Who says your USP can’t be bigger than your product?

Like Nike, if you can think beyond your immediate market and create a narrative that empowers the world, you’d get a USP that transformed a running shoe company into a global lifestyle brand.

The year was 1980, the start of the American aerobic fitness craze– think neon leotards, leg warmers, and brightly colored sweatbands.

At the time, Reebok had the largest share of the U.S. athletic wear market.

The British brand was riding high on the fitness trends of the time, which saw its annual sales jump from $12.8 million in 1983 to $1.82 billion by 1987.

That’s a surge of over 14,000% in less than 5 years.

While Nike wasn’t doing badly either at $1.71 billion annually, the company has been trailing Reebok in sales and market presence for nearly a decade.

Nike needed a bold strategy to escape Reebok’s shadow and become the market leader.

The Market Landscape

Reebok’s marketing was heavily focused on aerobics. The company targeted only the fitness-conscious demographic.

And like Reebok, most athletic brands at the time directed all marketing efforts to fitness-focused consumers.

A few others, who didn’t, stuck to performance-oriented marketing.

No brand was speaking to the regular people.

Nike saw this opportunity and wanted to become the brand that speaks to consumers of all fitness levels and backgrounds, from casual joggers to professional athletes.

The brand needed a way to communicate this value but what they ended up with was even better.

The USP

In 1987, Nike hired Dan Wieden, the founder of the Wieden+Kennedy agency to create Nike’s first major television campaign.

The campaign, developed by different creative teams, featured commercials for women’s fitness, walking, cross-training, running, and basketball.

Reflecting on its creation, Dan Wieden said:

“In reviewing the work the night before the client presentation, I felt we needed a tagline to give some unity to the work, one that spoke to the hardest hardcore athletes as well as those talking up a morning walk.”

“Creatives in the agency all questioned if we really needed it,” says Wieden.

“Nike questioned it. I said, ‘Look, I think we do. I believe we have too many disparate commercials that don’t add up to anything without a tagline. I’m not married to the thing. We can drop it next round.’ A lot of shrugged shoulders, but they let it ride.”

In a 2009 documentary, Art & Copy, directed by Doug Pray, about the advertising industry in the U.S, Wieden revealed that the line was inspired by the last word of death row inmate Gary Gilmore, who was facing firing squad and said, “You know, let’s do it.”

Coincidentally, the USP embodies Nike’s mission statement:

“To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.”

And as Nike’s co-founder Bill Bowerman once said, “If you have a body, you are an athlete.

The Impact

Talking about the impact, Wieden said:

“None of us really paid that much attention. We thought, ‘Yeah. That’d work,’ ” he says, adding, “People started reading things into it much more than sport.”

“The general public surprised us all,” Wieden continues. “Immediately Nike started getting letters, and phone calls, so did Wieden + Kennedy.

Here’s why…

The USP speaks directly to anyone who has ever faced self-doubt, procrastination, or fear.

It’s an inspiring call to action that works for elite athletes and weekend warriors alike.

Consumers see it as a universal message of motivation that goes beyond athletic performance.

Nick DePaula, an NBA feature writer at ESPN said:

“Not only was the slogan great, and also approachable and vague enough that anybody could apply it to whatever it was they were trying to aspire to do,”

“That campaign, along with those shoes (referring to the Air Jordan 3, the Air Trainer 1, and the Air Revolution launched with the campaign) in particular, sort of built the foundation for Nike to take off in the ’90s,” DePaula added.

From 1988 to 1998, Nike’s share of the American sportswear market increased from 18% to 43%. Sales also skyrocketed from $877 million to $9.2 billion globally.

By this time, Nike had become more than just a sportswear brand. It now symbolizes personal empowerment and breaking through barriers.

“Just Do It” inspired millions to lace up and chase their goals.

Today, Nike is the king of all sportswear brands in the world.

The company made over $51.5 billion U.S. dollars in sales in 2023, more than double that of second-place Adidas.

USP Example 2: Apple – Think Different

How do you revive a brand that’s on the brink of insolvency?

Think Different.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company he co-founded had hemorrhaged a staggering $1.87 billion in just two years.

Apple’s market capitalization had decreased from $1.8 billion to $1.6 billion, a brutal testament to its decline.

After years of not-so-good leadership under Gil Amelio, Apple was left with a portfolio of products that nobody wanted.

Journalists mocked their computers as glorified toys, incapable of “real” computing.

To illustrate how bad things were:

- Apple’s market capitalization had shrunk from $1.8 billion at its 1980 IPO to $1.6 billion by the end of 1997.

- Over the prior two years, the company incurred massive losses totaling $1.87 billion.

- Apple’s market share was plummeting, investors were jumping ships and the press had predicted Apple’s imminent demise.

The Groundwork

Jobs himself admitted, “The company is in worse shape than I imagined.” He said.

So something needs to be done and if anything, fast.

Over the next few months, Jobs embarked on a spree of radical reforms:

- Cut Apple’s bloated product lineup from 15 to 4

- Streamlined Apple’s retail chain and unified sales through an exclusive national dealer.

- Secured a $150 million investment from rival Microsoft, the deal ensured continued software support for the Macintosh

- Terminated the licensing deals that enabled other manufacturers to undercut Apple with Mac clones.

- Eliminated the fragmented profit-and-loss structure of individual business units and created a single P&L statement for the entire company.

While these were giant strides to turn the company’s fortunes around, Apple’s problem was beyond financials.

Steve was quick to realize it. He needed to do something about the soiled identity of the company.

The Market Landscape

Amidst Apple’s crisis, competitors like Microsoft and IBM thrived, but their advertising focused on product specs and functionalities.

This 1990 Microsoft Excel Ad is a classic example:

Taking inspiration from Nike, Jobs knew for Apple to survive, it needed to start talking about identity and value rather than products and specs.

As he stated:

“To me, marketing is about values. This is a very complicated world; it’s a very noisy world. And we’re not going to get a chance to get people to remember much about us. No company is. And so we have to be really clear on what we want them to know about us.”

The USP

In July 1997, Job rehired Lew Chow’s agency TBWA/Chiat/Day, the ad agency behind the legendary 1984 TV spot that introduced the Macintosh to the world.

This time, the agency’s job wasn’t to create another award-winning product campaign but to revive the company’s battered image.

This would be Apple’s first brand marketing campaign in several years. And the goal is to get the brand back to its core value.

Lew Chow’s team came up with the “Think Different” USP.

After weeks of several cheerless sessions with the creatives at TBWA/Chiat/Day, Job would timidly let the “Think Different” campaign fly. (Read the full story here)

The campaign featured iconic figures like Einstein and Gandhi. It celebrated the “crazy ones”- those who rebel against convention to change the world.

Beyond selling computers, it positioned Apple as a brand for rebels, dreamers, and innovators.

Upon launch, the campaign garnered mixed reactions.

The skeptics scoffed, critics had a field day, and Apple faithful were fired up, again.

But love it or hate it, it did exactly what it was meant to do. It got people talking about Apple again.

The brand that was gradually fading into the footnote of history became the talk of the town again.

And this time, in a whole new way

The Impact

The effects of “Think Different” were profound.

Despite having no major new products at the time, Apple’s stock price tripled within a year of the campaign’s launch.

In 1998, the company released its iMac G3, which embodied the spirit of “Think Different” with its bold, colorful design.

The iMac G3 ad creative was a complete departure from the industry norm. No feature listing or functionality lowdown, just pure identity selling.

The iMac would go on to become one of the best-selling computers in history, signaling the rebirth of Apple.

“Think Different” quickly became iconic, winning several commercial-of-the-year honors.

USP Example 3: Dollar Shave Club – Shave Time. Shave Money

Any market where consumers live in brand-name slavery is ripe for disruption.

You only need the right idea to make it happen.

When Dollar Shave Club entered the razor market in 2010, consumers were paying around $40 per month for blades.

On top of that, going in-store to purchase replacement blades was a challenge.

Razors were often kept under lock and key in stores due to the high theft rate.

DSC Founder, Michael Dubin saw this frustration and decided to address it.

But if Dollar Shave Club were to take on Gillette, which owned 70% of the razors market, it would need more than a great product.

Michael Dubin had the perfect idea- take away all the hurdles that made consumers jump through hoops just to buy a razor.

The Market Gap

The existing market model favored Procter & Gamble’s Gillette, who controlled pricing and distribution through traditional retail channels.

Then, consumers contend with multiple pain points in razor purchasing: exorbitant prices, inconvenient store purchases, and the constant challenge of remembering to buy replacement blades.

So DSC had just three things to do:

- Find a way to reduce the price of razor

- Make it easier for consumers to get and

- Take away the headache of razor replacement and possibly eliminate store trips

And it does it fantastically well.

Micheal Dubin introduced a revolutionary subscription-based razor delivery model that would:

- Cut out retail middlemen.

- Deliver re-fill razors directly to consumers’ doors, once a month or less often if they want.

- Slash the price of razors by more than half.

- Make buying razors as easy as clicking a button.

And that all, affordability, simplicity, and direct-to-consumer convenience.

While subscription models weren’t novel in 2010 (SaaS companies have been using them since the dawn of security software), Dollar Shave Club is one of the earliest brands to adopt the model in the D2C space.

The USP

DSC’s offer was simple: Get razors delivered monthly for as low as $1 plus shipping.

Now how do you sum up that in a single USP? Dollar Shave Club needed just four words to do it.

“Shave Time. Shave Money”

Let’s break it down, and you’ll see the genius:

- Shave Time: No more weekend trips to the store, no more awkward interactions with locked-up razor displays. We’ll ship fresh blades right to your doorstep every month.

- Shave Money: High-quality razors at a fraction of the competitors’ cost. You get the best-grade blades delivered for just $1.

It doesn’t get simpler than that.

This wasn’t marketing. It was a liberation manifesto for every guy tired of overpaying for hard-to-get razor blades.

The Impact

In March 2012, Dollar Shave Club released a YouTube video marketing “Shave Time. Shave Money”.

The video featured Dubin himself humorously selling the subscription-based razor delivery offers.

Thanks to a market already screaming for liberation, that video went viral and became an instant sensation.

On the day it was released, Dollar Shave Club’s server crashed from too many people wanting in.

In just 24 hours, they signed up 12,000 customers at $1 per month. That’s $144,000 in annual revenue overnight!

Within two years, Dollar Shave Club had captured 10% of the razor market, forcing industry giants to reconsider their business models.

DSC’s approach was so disruptive that it prompted major industry responses. Industry giants were forced to reconsider their business models.

Procter & Gamble launched its subscription service, Gillette on Demand, and Walmart also started its Beauty Box service.

Gillette was so threatened they sued Dollar Shave Club.

Their claim? Dollar Shave Club sourced razors from Dorco Co., a Korean manufacturer that allegedly utilized patented technology used in Gillette’s popular products like Fusion, Mach 3, and Venus razors.

At the most basic level, DSC is a pretty simple idea. “Founder and CEO Michael Dubin didn’t reinvent the wheel.

He simply created a convenient and affordable solution to a real, relatable problem shared by men everywhere,” as Ramona says in her post.

When asked about his business model, Dubin was frank and direct. He told Inc.:

“It’s not too hard to copy the techniques of the big guys. Razor technology is out there for anybody to duplicate. … There’s a real sense of relief that someone is finally doing something about the price of name-brand razors. Our customers feel like they’ve decided to liberate themselves from brand name slavery.”

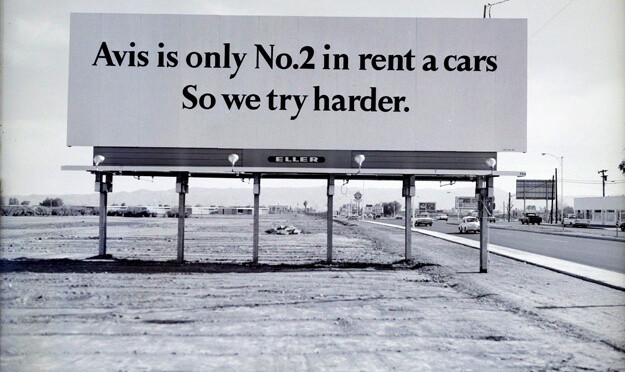

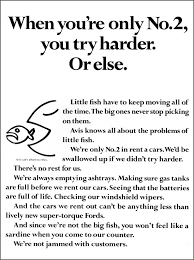

USP Example 4: Avis – We’re number two. We try harder

What do you do when you’re not No. 1 in your industry?

For Avis, the answer was bold: you own it.

And sometimes, that’s exactly what it takes to become unforgettable.

It was a terrific 19th-century rivalry.

In the early ’60s, Hertz was the undisputed king of car rentals with 61% of the market share.

Avis was second with 29%.

This dominance came despite Avis’s innovative approach to business. They had pioneered the concept of airport-based car rentals in the mid-1940s.

The company saw the growing needs of business travelers who wanted to fly in, drive to meetings, and fly out the same day.

While Hertz had initially dismissed this airport-focused strategy, they eventually followed suit only to beat Avis at their own game.

After trailing far behind for almost a decade, Avis was desperate to increase its market share.

In 1962, Robert C. Townsend, Avis president hired famed Madison Avenue ad man Doyle Dane Bernbach.

But what did the company have to compete?

On paper, Avis had practically, absolutely nothing over Hertz.

Newer fleets. Lower rate. More locations. Hertz dominated.

The Market Landscape

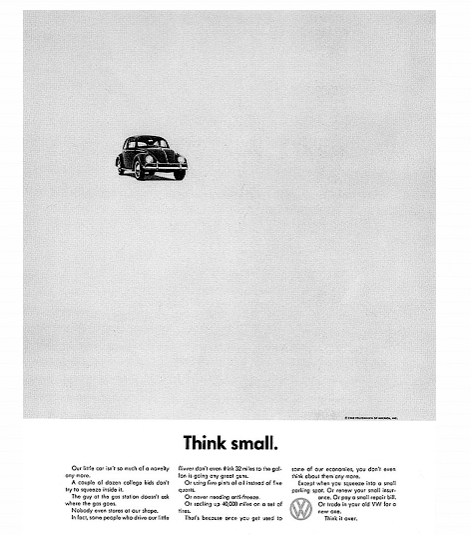

The early 1960s marked a crucial shift in American consumer psychology.

People were growing weary of the bigger-is-better mentality that had dominated 1950s consumerism.

There was a growing appetite for authenticity and a willingness to question whether market leadership automatically meant superior service.

This subtle but significant shift created an opportunity. Legendary ad man Bill Bernbach had picked up on this shift.

Americans were ready for something more humble, something that poked fun at authority.

You could see it everywhere. While American car companies were making massive, flashy vehicles with ridiculous tail fins, DDB was telling people to “Think Small” with the Volkswagen Beetle.

They even dared to call it “ugly but it gets you there.” and the public ate it up.

Bill Bernbach Agency and DDB pioneered these judo-style campaigns, which turned what seemed like a brand’s weakness into its greatest strength.

So, it wasn’t a mere coincidence that Avis turned to the same agency when in need.

The USP

DDB began their work for Avis by asking one pivotal question:

Why would anyone choose the second-place rental car company?

DDB copywriter, Paula Green was assigned to Avis,

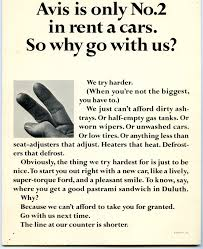

When Paula Green expanded the campaign to include the line, “Avis is only No. 2 in rent a car. So why go with us?” it sparked objections within the agency.

Many felt that highlighting the No. 2 position came across as a self-deprecating weakness.

To address these concerns, Green instructed the research department to test the idea by presenting the ads on 3×5 index cards to travelers at airports and other locations.

The results? Well, they weren’t exactly encouraging – 50% of people thought being “No. 2” meant “not as good as.”

Bernbach asked, “What about the other 50%?”

Through extensive research and interviews, they uncovered a crucial insight—consumers weren’t looking for grandiose promises.

They wanted dependable service, convenience, and a brand that valued their loyalty.

Armed with the knowledge that half their audience saw potential in being number two, they managed to convince Avis to take the bold leap.

Paula Green, DDB copywriter

She created the “We Try Harder” tagline, a phrase that eschewed bravado in favor of honesty. Green explained, “It went against the notion that you had to brag,” noting that the slogan reflected her own experiences of persistence in a male-dominated workplace: “‘We Try Harder’ is somewhat the story of my life.”

In subsequent years, Avis rolled out campaigns such as :

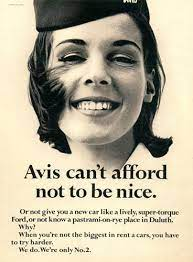

“Avis can’t afford not to be nice,”

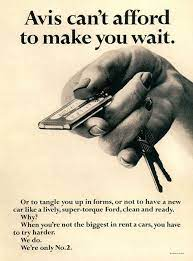

“Avis can’t afford to make you wait,” and

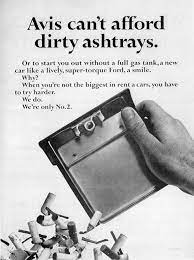

“Avis can’t afford dirty ashtrays.”

The Impact

The “We Try Harder” campaign was an instant hit.

Within a year, Avis turned a $3.2 million loss into a $1.2 million profit, its first in over a decade.

From 1963 to 1966, the company’s market share jumped from 29% to 36%, while Hertz’s dominance eroded from 61% to 49%.

While Hertz initially dismissed the campaign, by 1966, it could no longer ignore its impact.

The company responded with its own counter-advertising with the title:

“For years, Avis has been telling you Hertz is No. 1, Now we’re going to tell you why.”

Further retorts followed:

“No. 2 says he tries harder. Than who?” And “Hertz has a competitor who says he’s only No. 2”

But the damage had been done.

Avis was able to project Hertz as a brand that had grown complacent due to its dominance, while Avis was ready to go the extra mile to earn every customer’s trust.

The campaign was so successful that Avis kept using “We Try Harder” for over 50 years.

USP Example 5: Domino’s – 30 Minutes or It’s Free guarantee

Here’s how a struggling pizza shop quickly turned into one of the fastest-growing chains in the world.

If you grew up in the era of DoorDash and Uber Eats, you can’t possibly imagine a time when food delivery was a shot in the dark.

Today, you can track your delivery driver’s every turn.

You may want to thank technology for that, but please, thank Domino first.

Follow me to Detroit in the late 1960s.

Two brothers, Tom and James Monaghan were running a small pizza shop called Domino’s, and things aren’t exactly going great.

They’re just another face in a crowded market, struggling to make ends meet.

Sure, they had great pizza, but so did everyone else.

The Market Landscape

The pizza market of the 1970s was a sea of sameness with local pizzerias dominating neighborhoods.

Pizza Hut, the market leader, focused on dine-in experiences and signature pan pizzas, while smaller chains vied for attention through variety and price.

While pizza delivery existed, it was a “get there when we get there” kind of deal.

Orders often took too long to arrive, leading to cold or soggy pizzas that frustrated customers.

Consumers didn’t just want pizza, they wanted it fresh and delivered on time.

Tom Monaghan saw this unmet market need.

He decided to position Domino’s as the company that deliver pizza faster than local pizzerias.

His strategy?

Introducing a radical delivery promise that would completely transform customer expectations about pizza delivery.

The USP

In 1973, Domino’s launched the game-changing “30 Minutes or It’s Free” guarantee.

The USP didn’t just emphasize speed.

It subtly highlighted quality (fresh, hot pizza) while eliminating risk for customers (or it’s free).

At this point, Domino’s wasn’t just selling pizza. It was selling peace of mind.

- 30 Minutes: A clear, tangible guarantee that addressed the frustration of long wait times.

- Or It’s Free: A no-risk proposition that showed Domino’s confidence in its service.

To make the promise feasible, Domino’s streamlined its menu to a limited selection of pizzas that could be prepared quickly.

The brand also optimized its delivery processes. It deployed a hub-and-spoke business model where each store served a defined delivery radius.

Other notable operational changes Domino employs include:

- Strategically placing stores to ensure better coverage of delivery areas

- Developing new cooking techniques and delivery systems

- Creating detailed training programs for drivers

- Investing in hot bags and other delivery innovations

The Impact

Calling this USP example a success would be an understatement.

Besides changing Domino’s fortunes, it redefined delivery expectations across the entire industry and became woven into the fabric of American pop culture.

The slogan was so deeply embedded in popular culture that even a decade after Domino’s dropped the guarantee, it played a central role in 2004’s Spider-Man 2.

But beyond pop culture, the numbers tell an even more impressive story.

- Domino’s exploded from 200 stores in 1978 to a mind-boggling 5,000 locations by 1989.

- The company became the fastest-growing pizza chain in the U.S., adding more than 1,300 stores in just two years during the mid-1980s.

- Within a decade, Domino’s sales exceeded $1 billion, making it the No. 2 pizza chain in the world, second only to Pizza Hut. (who had nearly twice as many stores) and had now geared up on delivery.

An unexpected perk for Domino’s was that even when deliveries were late, most customers rarely claimed their free pizza, often feeling it wasn’t fair to the drivers.

However, the story doesn’t end there. In 1993, Domino’s was forced to retire the guarantee after a series of lawsuits and safety concerns about delivery drivers rushing to meet the 30-minute deadline.

One particularly tragic lawsuit involved a delivery driver who caused a fatal accident while trying to meet the time guarantee.

Domino’s eventually phased out the “or it’s free” guarantee, but by then, the brand had established itself as the leader in pizza delivery.

In 1986, Domino’s adjusted the guarantee to offer a $3 discount instead of a free pizza.

This change is famously referenced in the 2014 comics, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles when Michelangelo triumphantly declares, “Time’s up! Three bucks off,” after a delayed delivery.

Wrapping Up

From Nike’s call to action to Apple’s rallying cry for rebels, each unique selling proposition example we explored above proved a common point:

A great USP is bigger than the product: The most successful brands don’t just sell features. They sell identities and movements that customers want to be part of.

Now, it’s your turn.

So, ask yourself: What makes your brand different? Why should customers care?

When you can answer that in a way that sparks emotion and inspires action, you’ll have a USP strong enough to shape an industry, and maybe even build the next billion-dollar empire.

And if you aren’t sure where to start, We’ve created this comprehensive guide on how to create a unique selling proposition for you. Check it out.